Why the Paperwork Reduction Act needs to go, Part 2

We're the only country that has tried to reduce burden this way, and it hasn't worked. Especially with capacity being gutted, we should learn from what the rest of the world is doing.

Yesterday, we kicked off Eating Policy’s contribution to PRA Week, an event comprised of commentary from Marina Nitze, Kevin Hawickhorst, and Alex Mechanick, and of course, the reactions of all of you choosing to read this instead of the more alarming news of the day. In our first post, we covered how the Paperwork Reduction Act has trapped federal government in the 1990s by stipulating approval processes for literal paperwork, how the real levers for reducing burden on the public sit far upstream, and how we can’t afford to burden a decimated federal workforce with compliance processes like these at the expense of mission-critical tasks. Today, we’re going to ask why the US is the only country with a PRA, and what that means about how to actually reduce burden.

The global view

As far as I can tell, no other country has a law equivalent to the PRA. My search has not been exhaustive, but I’ve looked into places like the UK, Australia, Canada, and the European countries, and not only is there no PRA-type law, there is not even a similar non-statutory practice. These countries struggle with digital transformation in much the same way the US does. While every country is different, their journeys from industrial era ways of working to the digital era have much in common. But the lack of a control point around information collection in a centralized, highly empowered office has not resulted in more information collection burden than in the US. If anything, other countries burden their people less.

As a scientific argument, this comparison leaves a lot to be desired — this isn’t exactly a randomized control trial. But given that one of the main justifications for the PRA is that without it, government agencies will run amok with unnecessary, burdensome forms, one might reasonably expect to see some negative impacts in other countries relative to the US. If anything, these PRA-free countries impose fewer burdens on their people. Take tax filing, for example. The United Kingdom, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Japan, Australia, Spain, Portugal, and Italy all have some version of a system we might call semi-automated, in which the data about earnings and liability have been pre-populated using data reported by employers and other sources, allowing filers to review and adjust their returns but not requiring them to figure out complicated and confusing data entry tasks. In some of these countries, tax filing for the average citizen takes mere minutes. In the US, filing is so frustrating and time consuming that anyone who can afford to pay a professional to do it for them will. Other services are similarly challenging. Applying for federal student aid has been so onerous that Congress tried to make it better by passing a law ordering the Department of Education to simplify the form. (It didn’t work). We are the negative outlier among our peers, and the PRA has done nothing to make that better.

While no other country has a PRA equivalent (and no US state either, for that matter), other countries certainly care about the problem of burden, and have different ways of trying to manage it. Let's look at two of them there, starting with the darling of the digital government world, Estonia.

Estonia’s Ask Once Principle

Estonia is famous for its “ask once” principle. The way it's popularly understood, it is literally illegal for the Estonian government to ask a citizen for information it already has. Imagine never having to fill in your address or date of birth again. Many assume that’s what the law states, but that’s not quite right. This practice derives from a clause in the Law on Public Information: "Establishment of separate databases for the collection of the same data is prohibited.” As Luukas Ilves, former CIO of Estonia explains: “The name of that law is a bit of a misnomer - it’s a broader legal framework for how we govern all public services. That framework aims to unify all the different layers of how we organize public services and government activity into overlapping layers that all connect to each other.” Government agencies don’t ask for the same information twice because it's illegal to store it twice.

In other words, Estonia keeps the burden down on its citizens by intervening far upstream from where the US does. Agencies aren’t coming to a central authority for permission to collect information because they already have almost all the information they need. Lives aren’t static, of course, so addresses must be updated after a move, children added when born, for example, but when necessary, information is updated once and available wherever needed within the administrative state. Administrative burden is so minimal as to be a non-issue.

This won’t happen in the US, for a few reasons. For one, Americans don’t trust their government, and believe that frictionless sharing of information enables all sorts of intrusive overreach, a view fed, ironically, by the irritation of constantly filling out the same information in multiple forms. For another, that horse left the barn a long time ago. The US has been “establishing separate databases for the collection of the same data” for…centuries, I guess, depending on your definition of a database. Estonia became an independent country again in 1991, making its current incarnation approximately as old as a pair of boots I bought when I graduated college. The best we can hope for, given our legacy infrastructure, would be for agencies to tackle the technical and legal challenges to data sharing among themselves, challenges that are not helped by a risk averse culture in which it’s always safer to say no to data sharing even when it has obvious benefits, and the low technical capabilities of US government generally.

The Service Standard Approach

It’s those capabilities that are the key to another approach to burden reduction, one that started in the UK but has spread to Australia, Canada, Germany, and probably others I’m not aware of. In 2013, the UK’s Government Digital Service launched the first version of its Digital Service Standard. The GDS had only recently been created, partly spurred by the failure of a project in the National Health Service (NHS) that had originally been projected to cost £2.3 billion, but ballooned to an estimated £12.4 billion over ten years, and was entirely scrapped in 2011. In the letter that reformer Martha Lane Fox wrote to cabinet minister Francis Maud calling for the creation of the GDS, she recommended “Appoint[ing] a new CEO for Digital in the Cabinet Office with absolute authority over the user experience across all government online services (websites and APls) and the power to direct all government online spending.” Absolute authority over the user experience of all government online services turns out to be a tall order when the bureaucracy responsible is as massive and sprawling at as the UK’s (or the US’s for that matter), but the Digital Service Standard was intended to be one way of exercising that authority, and it had an enormous impact on the UK’s journey towards digital transformation.

Digital transformation is a terrible buzzword that feels like it fell out of a slide deck from an overpriced consultant, but I don’t have a better word so I will use it. It’s not digitization — making digital equivalents of existing processes — and it’s not what most people mean by modernization, which is moving the software to manage an existing process from mainframes to the cloud, or from other old platforms to new ones. Digital transformation means rethinking how we achieve our policy goals and serve the public in the digital era. At minimum, it reenvisions processes, sheds legacy ways of working, and, as Tom Loosemore says “meets the public’s raised expectations.” It’s not a computer screen strapped to a seat back in a taxi; it’s Uber or Lyft. Digital transformation happens to offer — you guessed it — dramatic reduction of burden on both users and service providers. It’s not only easier to hail and pay for a Lyft than it is to get a taxi, it’s easier for the Lyft driver to find you without radioing back and forth with dispatch.

Digital transformation is much harder to do than sending all forms through a central office responsible for legal compliance, but the former actually reduces burden whereas the latter seems to increase it. Listen to what Brits have to say about the GDS’s Lasting Power of Attorney service, for example, or their application for Carer’s Allowance, which removed 170 questions from the legacy process. Both went from the kind of process you hire a professional to guide you through to a task you can complete with confidence unaided. Neither was subject to anything resembling the PRA, but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t some intervention or support from a central office. Before these services could launch, the teams responsible had to demonstrate that the new services were consistent with the Digital Service Standard. But what made these services better wasn’t the review itself. What made them better was the investment the UK government made in its service design competencies and capabilities so that it could meet the standard before it ever got to the review. Instead of intervening at one choke point, creating a gate before something can launch to the public, the UK has decided to work far upstream. Instead of instituting rules and compliance, they have focused on hiring and training appropriately skilled staff. Instead of lawyers and others with a compliance mindset, the suitability of a form is judged by service designers, user researchers, and product managers whose job it is to understand the needs and constraints of people who will be using the form.

As Kevin’s recent post reminds us, the US used to do this. His description of Forms Control sounds a lot more like a Service Standard than a PRA review. For one, Forms Control wasn’t based in statute. For another, it focused on enabling public servants with the tools and skills they needed to both design usable, consistently understandable forms and simplify the underlying processes those forms served as input to. Forms Control was very popular even outside of government; businesses requested the Simplifying Procedures through Forms Control manual so often that it was reprinted as a book and became a bestseller!

The key point that Kevin makes in this post, as he has in several other excellent posts, is that the federal government used to invest far more in developing their people through training, guidance, and setting clear expectations to achieve goals like burden reduction than it does today. His post on the Eisenhower era practice of Work Simplification blew my mind, because what he describes is so like the practices digital transformation advocates have been pushing, and it was de rigueur, an expected competency not of specialized “digital services experts” as it is today but of all middle managers. Here he describes a slice of Forms Control:

The functional file (above) contained copies of forms grouped by major purposes. It might, for instance, have a group called farm aid forms: this group might include a form that the public might fill out called application for aid, and also include a form that only the agency filled out called review of aid application.

This file would be used to drive operational improvements. Managers were required to periodically look through the related forms to see if duplicative forms might be combined. But more than this, the functional file showed public-facing paperwork side-by-side with purely internal paperwork. Managers were required to analyze ways to improve their office procedure to better use the information the public submitted, and conversely, to stop asking for information that the agency did not actually intend to use.

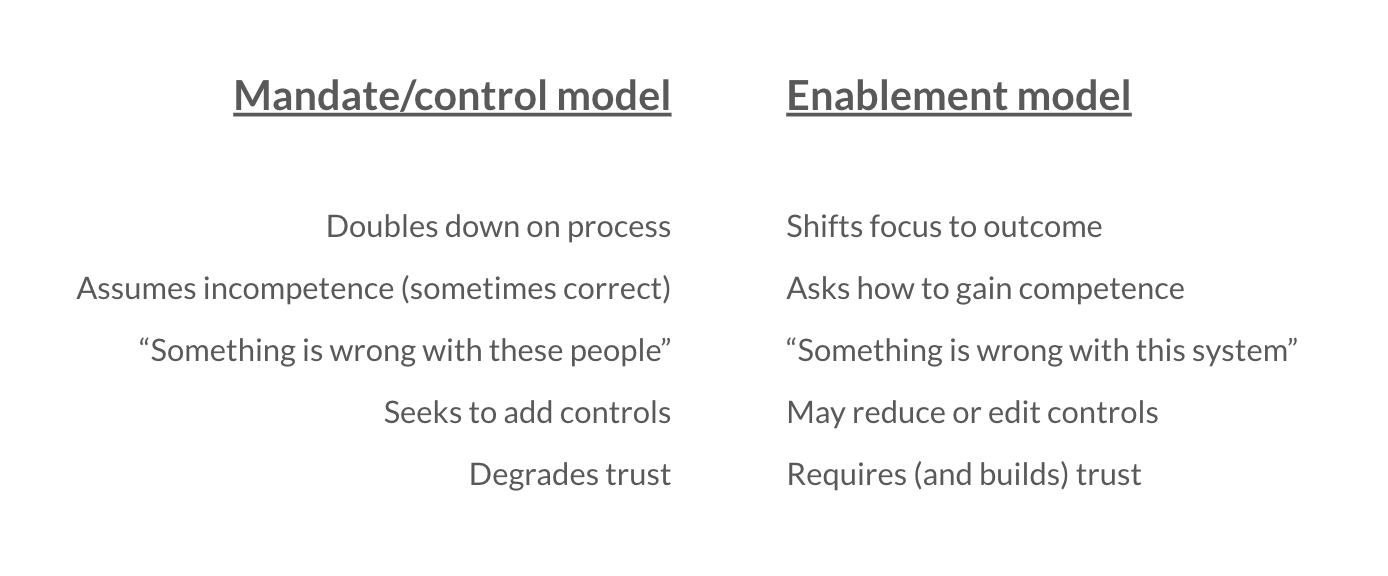

Without putting words in his mouth, I believe Kevin has landed on the same conclusion I have: that in pursuit of burden reduction and many other goals, we are trying to rely too heavily on rules and ways to enforce those rules and underinvesting in the development of critical competencies where the work actually happens. Here’s a slide I often use with Hill staffers who ask me what they should do to improve the performance of an underperforming agency:

Legislative staffers at all levels of government tend to believe that mandates and constraints are their main tool, creating a classic “when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” situation. But there are many levers available to them in the enablement model, including writing bills that focus on outcomes and refrain from overspecified process, removing constraints on agencies, engaging in routine, curious, non-outrage-driven oversight, and supporting (and even funding!) the modern versions of efforts like Eisenhower’s Work Simplification and Truman’s Forms Control. While it would be great to see efforts like those last two coming out of central offices like USDS or GSA, DOGE’s has a very different purpose, which leaves hill staffers and their bosses to figure out how to support and encourage the agencies they oversee to invest in their own capabilities — a tall order given the current cuts. (And another reason, of course, to take as much low-value compliance work off agencies as possible, starting with PRA review.)

A US service standard?

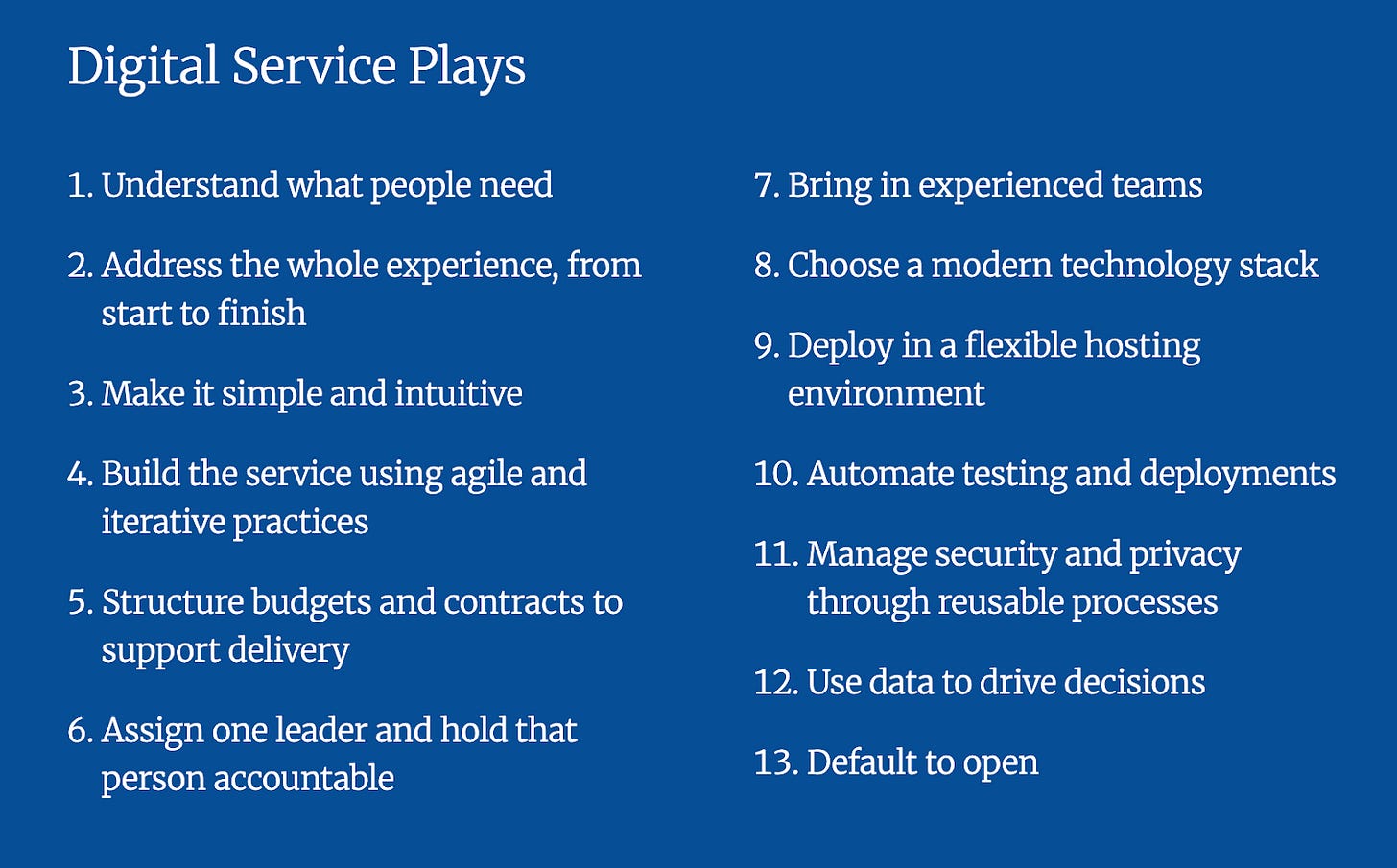

If Work Simplification and Forms Control operated a bit like the GDS’s Service Standard, one might ask if the US has had anything similar. Well, yes, sort of. When I worked in the White House in 2014, part of our remit was to establish the guiding principles for what became the US Digital Service (USDS). A few of us, including Haley Van Dyck, Ryan Panchadsaram, and Casey Burns wrote something called the Digital Services Playbook, heavily inspired by the UK’s Digital Service Standard. The Playbook never had the weight of a standard – there was neither appetite nor resources to train agencies in its plays other than through exposure to USDS teams and their ways of working. There was certainly no attempt at enforcement — USDS does not have that authority (or didn’t then — it is unclear what authority the US DOGE Service has now.) But it did get published on the website of the Federal CIO, an office that does, in theory, have some degree of control over agencies’ forms through spending approvals, but has more recently exercised its influence through efforts like Biden’s Customer Service Executive Order and coordinating what’s called High Impact Service Providers (key agencies) to bring that vision to life.

On a practical basis, mind you, such authority would have been pointless without the kind of investments in training and staff development that Eisenhower and Truman saw fit to make — developing the competencies agencies needed to reduce burdens. The literature covering PRA routinely calls for more investment in training agency staff on the do’s and don'ts of the PRA. There’s a lot to learn! But again, we make choices. We could invest in training public servants on an invented and unhelpful procedure, or we could train them to make better, less burdensome services for the public. At the moment, tragically, we are choosing neither. But in the longer run, we should stop creating and nourishing what the Brits would call “government needs” at the expense of meeting user needs — the needs of the American public.

Defenders of the PRA might concede that a service standard, backed by a strong internal core competency of service design, is a better way to reduce burden than review for compliance under the PRA, but might also argue that since we have neither a service standard nor the infrastructure to build that core competency, especially with USDS having been effectively replaced by DOGE, the PRA is still needed. That’s a bit like saying because no modern doctor is available to see a patient, we should continue administering leeches. Individual OIRA officers can have positive impacts, of course, and I honor their efforts. But the cost to the agencies in terms of effort and time, and the impact of the delays, is simply not worth the tradeoff, as Marina brings to life so well. The remedy is simply the wrong one. Even absent a better alternative, like the Estonians’ ask once policy or the UK’s service standard and attendant competency development activities, removing the barrier of the PRA is still a net positive to basic capacity, which is in desperately short supply and getting scarcer by the day.

I don’t want to pretend that freeing agencies from PRA review would solve their capacity problems. DOGE is gutting agencies. There simply won’t be enough people to do the work, and changing this law wouldn’t remove enough work to get us back to anywhere near the right balance. But it is a step lawmakers can take in the right direction, regardless of their views on DOGE or the current administration. Republicans should support action on the basis of shrinking government, even as Democrats seek to provide some relief to beleaguered agencies. I also don’t want to call for rolling back the PRA solely in response to the current moment. It was a problem before DOGE, and should have been addressed then. Should our current leadership continue to ignore it, it will still be a problem long after DOGE is gone.

In the end, so much in government comes down to the question: what do we ask civil servants to do? If the answer is “ensure compliance with this law,” the day to day of their work will ultimately diverge from the original goals of the law. It will end up meaning “learn and follow a whole bunch of obscure, persnickety rules that make sense to no one outside this ecosystem, but can be endlessly debated by all parties within the ecosystem.” This is how government stops making sense to the public whose support it ultimately relies on. The more we can ask civil servants to do the actual thing, instead of a poor proxy for the thing (one that even further degrades in its utility over time), the stronger the institution will be in the long run. Stop asking our federal workforce to comply with the Paperwork Reduction Act and start asking them to reduce paperwork. The two are not at all the same.

Thanks to Luukas Ilves, David Eaves, and Andrew Greenway for their help on the global perspective here.

The UK’s Tell Us Once service is another good example - it reports a death to most national and local government organisations in one go e.g., taxes, benefits, pension, passport, driving and vehicle licenses, electoral register, disabled badge.

In addition to being a more recent state, Estonia also has the advantage of being a unitary rather than federal state for its "Ask once" policy. I imagine that most people do not consider (or care) whether they are providing information to their state or federal government, let alone the different agencies or departments within the federal government.