Schedule F's uncomfortable truth

Trump's stunt to test public servants for loyalty would only make our civil service problems worse. But there is a problem.

If Trump wins the election, it seems that we will see Schedule F return. For viewers just tuning in, Trump issued an executive order creating a new category of federal employee just before he left office in 2020. The order created a new job classification (F) for "confidential, policy-determining, policy-making, or policy-advocating" positions, and removed standard civil service protections for these positions. Essentially, it was a way to reclassify some public servants into a new status so the administration could fire them without going through the process civil service rules require. But Biden reversed it as soon as he took office. So Schedule F was around for a matter of days and never used. But it almost certainly will be if the election goes Trump’s way.

Schedule F is a terrible idea. I won’t go into the nightmare scenarios it could enable. Others have covered this. But often it makes anti-Trumpers dig their heels in and deny the problems in our civil service rules, for fear of validating Trump’s non-solution. This is a bad response to a bad idea. Ezra Klein’s column yesterday frames this election as a battle between the Guardians Against the Counterrevolutionaries, those who want to defend our institutions vs those who want to destroy them. Maybe he’s right, but that framing leaves no room for people like me. The institutions are sometimes hard to defend, but that doesn’t mean we don’t need them. We need them fundamentally reformed.

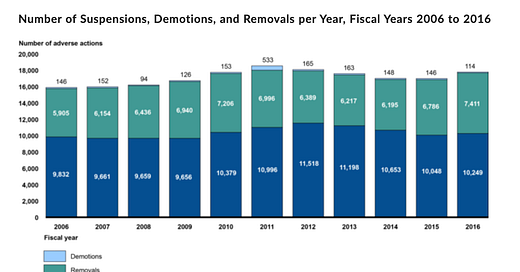

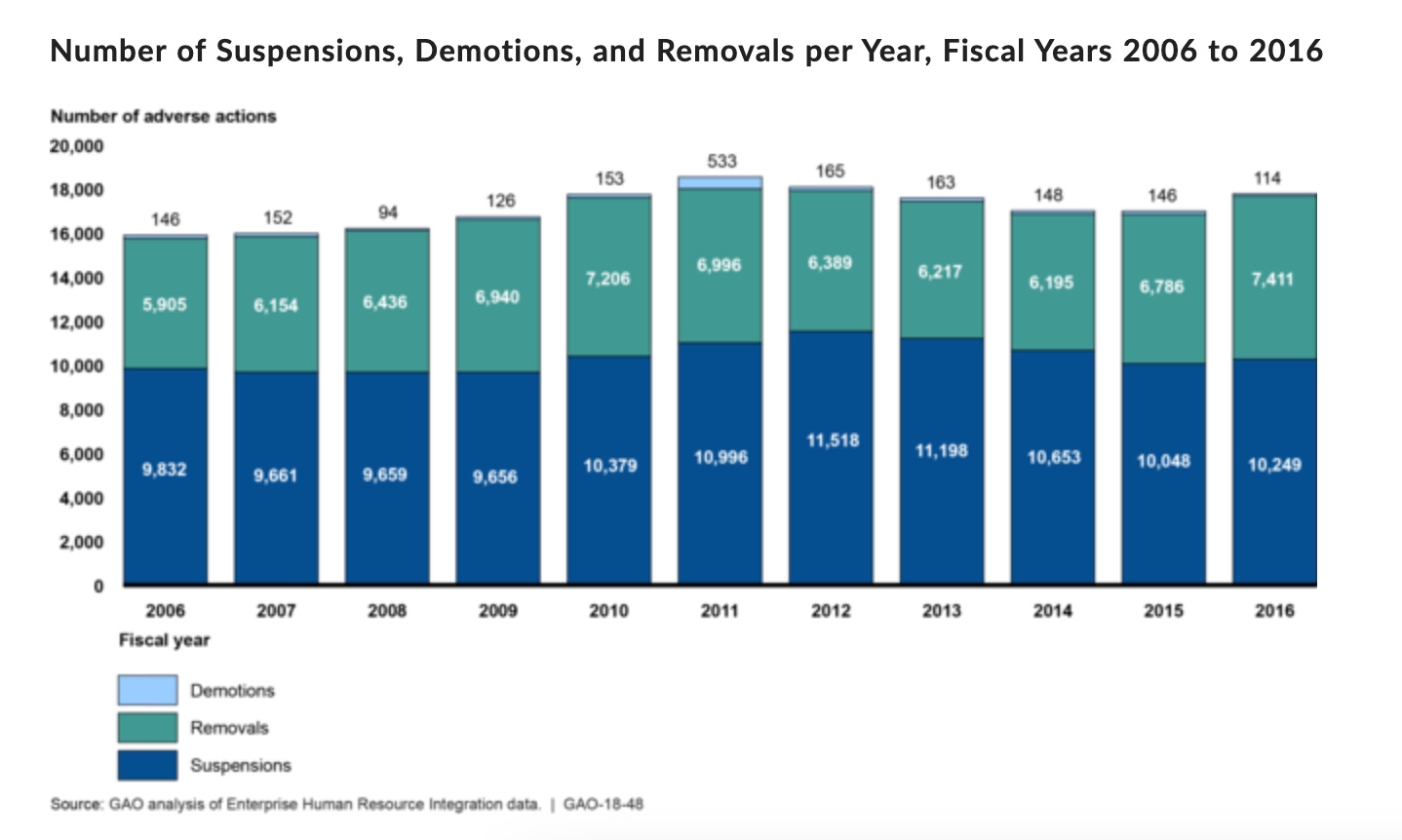

Jenny Mattingly at the Partnership for Public Service published a good op-ed earlier this week that explains the actual problem that actually needs solving, which is that it’s too hard to fire federal employees for poor performance. (Schedule F isn’t designed to address poor performance. It’s designed to remove people who don't pass a test of loyalty to the new administration.) One of many useful stats Jenny quotes is that “according to the Government Accountability Office, nearly 17,000 federal employees are disciplined or fired for misconduct annually.” But wait, so is that a lot? A little? What?

The data she points to distinguishes between suspensions, removals, and demotions, and it’s only from 2006 to 2016. I couldn’t find more current data. But over those eleven years, the federal government actually fired (not just disciplined) approximately 6,400 employees a year. I’m going to assume the denominator here is 2 million, since that’s the number generally given for the size of the federal workforce, and it hasn’t changed that much in recent decades. That gives you a rate of .32%. The same rate in the private sector seems hard to nail down, but I found estimates of 1.2%.1 That would mean that the federal government fires people approximately a quarter as frequently as the private sector. And the private sector does layoffs too, and though they aren’t technically about performance (many high achievers get caught in these actions too), they’re another way to remove poor performers that government doesn’t really have. It’s pretty clear we’re employing too many people who can’t or won’t do the job.

When I was interviewed on the Ezra Klein show, he asked me about firing underperformers in government. I was hesitant on the topic, and said that being able to hire better should be a higher priority. But that response came in part from wanting to come off as a champion of public servants, which I am. I think the best of the government workforce is truly amazing. But those who are pulling their weight are hugely frustrated by how hard it is to hold low performers accountable, and how hard it is to hire on the basis of skills instead of how well candidates can cut and paste from the job description into their resumes. According to a Merit System Protection Board study, “three-quarters of supervisors of unacceptable performers reported attempting 10 or more different approaches for addressing the performance problem of their most recent poor performer.” The same study concludes that even the “most effective” methods of resolving unacceptable performance available to federal managers are effective in “less than half of cases.” This state of affairs affects productivity, retention, and motivation, as public servants hired to fulfill a public mission find themselves entirely consumed with wrangling an ineffective and inefficient HR system. As one State Department employee told me recently: “If you have someone who’s not a good fit or incompetent or just not really interested in participating, there is not much you can do about it. So it leaves me wondering what’s more important: HR’s processes or accomplishing the task the US government has asked you to fulfill?”

It would be easy to assume that public servants abhor Schedule F. But I know at least one who is voting for Trump because of it. It’s not that he thinks it’s a perfect idea, only that it’s something, and after years of no movement on this front, and of becoming increasingly frustrated trying to serve the mission he’s committed to, something is better than nothing. Democrats, he feels, have signaled zero appetite for giving him and his peers the ability to hold their teams accountable and get the job done. He’ll take what he can get.

If Trump wins this week, I don’t think my Trump-voting public servant friend is going to get what he wants. He’d have to prove his low performers were in “policy-determining” roles in order to reclassify them, and the legal apparatus is going to fight him on that. If Harris wins, I pray that Democrats try to win my friend’s vote, because he’s right. Public servants deserve a system that works, and so do all of us who rely on them.

Reader Chase Houlbrouk writes: “I think the BLS JOLTS data (Job Openings and Labor Turnover) is the more current data you're looking for, and it confirms what you've written in the post. Other than an outlier in 2020, private layoff/discharge rate ranges from 1.1%-1.3%, with federal government ranging from 0.2-0.4% and state government ranging from 0.3%-0.5%. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_03062024.pdf (Table 24, p. 35)” Thanks, Chase!

Having just completed the process to terminate a civil service employee, it's bewilderingly complicated and I'm not really sure it even benefits employees, some of whom stay in a role where they are clearly unhappy or unqualified, long after it was time to move on, because of this perceived sense of "safety".

When you pair this with how hard it is to do a merit-based increase or promotion, you have a system where there is no carrot or stick. It's hard.

When an organization doesn’t fire underperformers the culture slowly spoils over time. Let’s say every year, 1% of the employees would be fired in the public sector, but aren’t. Each year the amount of underperformers increases. Some teams just fill up with these people. The best employees don’t want to work with these coworkers, and leave. Good managers get frustrated because they can’t build a good team. Good workers get frustrated when they’re paid less than the guy who does nothing.

It feels like you are being “the nice guy” when you keep around someone who’s bad at their job, but you are also being unfair to their hard working teammates.