Public input is not user research

OMB is right that we need new methods of engaging with the public that don't allow for capture by special interests. Service design provides some models.

Michael Lewis once said “You never know what book you've written until people start to read it.” The topic where I’ve most felt this in relation to Recoding America is around user research. Many times since the book came out, public servants have told me something to the effect of “I know user research is a good thing, but the process is so painful for us. Putting our plans out for comment or holding public meetings results usually just stops us from doing anything. It’s so demoralizing.”

This is the point where a) my heart breaks and b) I realize that no matter how hard I tried to distinguish between public input and the practice of user research in the book, I didn’t try hard enough. I’d been meaning to write a sort of clarification, but it’s been on the back burner for while. But OMB recently issued a Request for Information around Public Participation and Community Engagement, (PPCE)1 so I’m using this as an excuse to get this post up. Apologies in advance: this one is long.

The Shadow of Moses

Before we dive into the differences between public input and user research, which I think is relevant to OMB’s RFI, I want to address why OMB might be asking for this input on input in the first place. I have no special knowledge of their particular motivation, but there are lots of areas where public input is quite controversial, dare I say even problematic these days.

Imagine you live in a city where very little housing has been built for decades despite growth in the population, and that increasingly limited supply has driven up prices and is driving out the working class. This becomes such a problem that there’s a clamor for leadership, and the city elects a mayor and a council who promise to address this. They pass legislation to make it easier to construct new housing and set targets for building. But whenever a development is being considered, NIMBYs block it through the public input process (and others, to be fair). The democratic process, in which everyone had a chance to have their say by voting for pro-building leaders, decided on one thing. But the public input process, in which people with the time, money, and awareness to participate get a bigger say, effectively decides the opposite. You can see how this can be both anti-democratic and often anti-equity: the people with the least resources and insider knowledge have the least say.

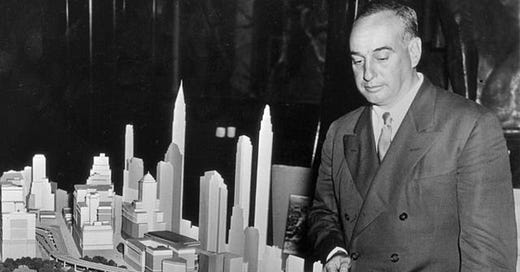

That’s both an age-old narrative and a relatively new one, in the sense that a different narrative has dominated for the last several decades: the Robert Moses story. Reading The Power Broker, which chronicles Moses’s cruel destruction of low-income neighborhoods in New York for most of the first half of the last century in favor of a freeway binge that locked the city out of the public transit infrastructure it needed, in some cases forever, there are places you will want to cry. I spent my teen years in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx; what he did to parts of those areas broke my heart. What he did to the people who lived in those places is unforgivable.

Of course, the point of The Power Broker is how Moses played everyone – governors, mayors, councils, civil society groups, the press (everyone, of course, except the people whose lives he destroyed, whom no one really listened to them until the sixties) – to essentially steal the power he needed to conduct his devastation entirely – and I mean entirely – unchecked for decades. Reading the book, I gasped at the third or fourth time legislators passed his bills without reading them, when at that point they should have known he was sneaking in absurdly unaccountable governance structures that give him control far beyond the reach of democratically elected leaders. For the love of God, people, READ THE BILL! It is unsurprising that we’ve tried to create a world in which Robert Moses’s crimes can never happen again, but he was kind of exceptional. His power source was far upstream from the public input process. By the time someone like Moses gains the kind of power he did, the solution no longer lies in a better public input process. That input would go nowhere anyway.

Public input today lives in the shadow of Moses and other (legal) crimes committed largely against poor people and people of color. But to say we’ve over-corrected and the pendulum needs to swing back is to be stuck on a narrow spectrum between listening and not listening. Those are not our only choices. I believe that may be what OMB is getting at when they requested this comment. We need to understand how to listen to and meet the needs of the public without inviting capture by special interests.

I hope OMB gets a lot of good answers to their RFI from people much more knowledgeable about PPCE (public participation and community engagement) than me. This is an entire field of expertise, and it’s not mine. I’m also not an expert in service design, but I see ways in which the practices of service designers might offer lessons for PPCE more broadly. And this whole space of how we listen to the public – whether in designing policy or services or in allocating resources or protections – needs a big refresh if government is going to effectively address the crises we face.

What is user research?

One of the service design tools that I think is relevant here generally falls under the term “user research,” though “customer research” is increasingly used as well. User research (we’ll use that term here for convenience) comes in a lot of forms, and I won’t attempt to describe the whole range of techniques used, but one of the several examples from Recoding America is an interview two service designers from the Department of Veterans Affairs conduct with a veteran named Dominic. Mary Ann Brody and Emily Tavoulareas ask Dominic to try applying for veterans’ benefits using the existing online application and watch where he clicks and what happens, gently prodding him to narrate his experience as it happens. They find that he’s very comfortable with the website, having navigated it dozens of times before in previous attempts to apply (none of which have worked). But they also see that his computer (like most others outside the VA itself) is not set up with the exact combination of Internet Explorer and Adobe Reader (both outdated versions) that is needed to load the form he needs to fill out.

When he clicked the link and the error message appeared as usual, he was unsurprised. He tried clicking a link in the error message and got another error message, this one about his connection not being secure (“Attackers may be trying to steal your information!”). In the recording you hear Mary Ann asking dryly, “Is this what you expected to happen when you clicked on that?” “That? No,” Dominic replies. “It’s like it takes you around the corner and over the meadow and tries to lead you into a back door that’s blocked with spikes and IEDs.”

Mary Ann and Emily don’t have a set script for this interview; they’re not running him through a pre-determined set of questions, but rather trying to understand his general life circumstances (which they learn about in a conversation before he starts navigating the website) that affect how is able to interact with the VA — in other words, understanding his particular needs and discovering why the VA’s current offering doesn’t meet those needs. Here’s more on needs from the book:

User needs aren’t necessarily all that complicated. Some of them become apparent through observation. After spending the day in a school vaccination clinic, a colleague of mine quipped: “Every time you add a question to a form, I want you to imagine the user filling it out with one hand while using the other to break up a brawl between toddlers.” Applications for government benefits might be completed under similarly chaotic circumstances. Users who have a lot else going on in their lives need to be able to apply for the service without an undue burden of time, technology, and cognitive overhead. If they’re asked for documentation, the documents need to be ones they have access to. If they need to correspond with the program, there has to be a way for them to do so even if they lack a stable mailing address. If they have family who are undocumented immigrants, they may need reassurance that applying for a program won’t get them or their relatives in trouble.

Few of those needs will be mentioned in a policy document. Few of them will come up in a formal notice-and-comment process. They reveal themselves through the practice of user research, to those who are present, observant, and respectful. (Physical presence is usually the best kind, though much excellent user research is done over the internet.) They emerge when you get out of the office, knock on doors, and literally meet the users where they are. They reveal themselves when we set aside our assumptions about what would work based on our own experience and instead test and measure what works for others.

There are many more kinds of user research, and they don’t all fit neatly into categories. According to Code for America’s Qualitative Research Guide, which catalogs six distinct methods, Mary Ann’s interview with Dominic is a combination of an in-depth interview and concept testing (in which you watch someone try to use a prototype of a redesigned service, like the one Mary Ann offered to Dominic after the legacy application failed. The new version was much easier to use, and wasn’t “blocked with spikes or IEDs.”) Think of these and other methods as a broad set of tools you can use to better understand the needs and circumstances of people you are serving.

Though we think of these tools are in the hands of service designers, it turns out they are very powerful in a policy context as well. Policy analysts are often trying to make sense of quantitative data, and qualitative user research provides much-needed insight into what those numbers actually mean. Much policy failure can be attributed to its many untested assumptions about the people who will interact with it both inside and outside government; an ongoing practice of user research can help debunk those assumptions before they’re codified in hard-to-change policy. (Tom Loosemore’s question “Why is policymaking educated guesswork with a feedback loop measured in years?” should be blazoned on the walls of policy offices.) To the extent OMB is looking for novel PPCE practices to better inform policymaking, they could be looking to these adjacent fields of service design, product management, and user research for inspiration.

Active vs passive

There is a key difference between the tools service designers use to understand the needs of their users and the classic process of public input. The former actively seeks out representative users, while the latter relies on a passive mechanism of hearing whoever wants to speak.

When Mary Ann interviewed Dominic, she and Emily sought him out as representative of the kind of veteran whom they believed was struggling to apply for benefits. The process of finding him and others to interview is what’s known as “designing the sample.” To borrow from the Code for America guide: “We use a few methods to design research samples, often working with quantitative researchers, getting ideas from subject matter experts, and understanding priorities of focus from the team. It is important to be clear about what characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, and experiences must be represented in your sample and be tenacious about recruiting those participants.” This is fundamentally an active, intentional processes that a lot of thought and effort goes into.

This stands in stark contrast to a wide variety of practices that fit under the banner of “notice and comment.” Since the passage of the Administrative Procedures Act in 1946, federal agencies are required to post a notice of proposed rulemaking (usually in the Federal Register) and accept comments from the public before issuing or changing a regulation. This notice and comment process isn’t just a thing agencies have to do. The idea that you should inform the public and let them weigh in before major decisions are made is the basis for everything from public comment agenda items in city council meetings to those forms taped to the window of a store that’s applied for a liquor license that tell you where to go complain if don’t like the idea of more booze available on that corner.

Notice and comment procedures are table stakes. They're a necessary input into decision-making in a liberal democracy, but they are also both hugely insufficient and enormously prone to capture by special interests. To understand why, all you have to do is open the Federal Register and read (or try to) practically any notice of proposed rulemaking. You will make it about three sentences before you ask yourself, Who in their right mind would read this? And you will answer yourself: People who are paid to. I mean, God bless the four govnerds in each niche who do this for fun and/or in the actual public interest. And I don’t mean to denigrate the incredibly knowledgeable staffers at companies, non-profits, associations, and the like who work so hard to understand the ins and outs of these proposed rules and help steer government in the right direction – some of them are certainly represent the public interest. But for the most part, in notice and comment frameworks, the winner is whoever has the most money to fund staff to submit cogent and compelling comments to this abstruse thicket of words.

If it's a notice posted about a proposed regulation, a public meeting on a proposed development, or one of those “to file a complaint, go here” notices, the way you are getting input is passive. Let’s hear from whoever shows up. Yes, there are lots of ways in which government staff and and do conduct “outreach” to invite a wider community to participate, but the basic invitation is still “you come to us” (come to the federal register, come to the meeting at this given time) and “you engage on our terms,” as in Read this language you may not understand and write a convincing argument in this box, Fill out this card if you want to speak for five minutes at the meeting. The invitation may or may not be broadcast widely, but the barriers inherent in participating still hugely advantage those with the resources, training, and level of comfort to speak in these spaces. Who shows up is rarely representative of the group of people most affected by the decision to be made.

I don’t need to tell public servants this. They know it. They are the ones at the public meeting, looking out at the faces of wealthy or middle class homeowners eager to block the proposed higher density housing development in their city. They are the ones wishing that some of the people who work in lower-paid service jobs, or even the junior staffers on their own teams, both of whom are commuting from increasingly distant exurbs because they can’t afford to live in their city, would show up and speak on behalf of their interests. But the meeting is in the evening and in the city, and they’ve already started their hour and a half trip home so they can see their kids before they go to bed. The people who already own homes have walked over to City Hall after an early dinner and they’re ready for the fight.

To be crystal clear, the practices of notice and comment are not user research. According to the Interaction Design Foundation, user research is “the methodic study of target users—including their needs and pain points—so designers have the sharpest possible insights to work with to make the best designs.” I would argue that, while notice and comment is necessary, it is not methodic, it does a poor job of targeting users, and it rarely provides sharp insights. It is a summary of opinions, not an analysis of needs and pain points.

Nor is much of what passes for “user testing” in government. If you’re designing a form, service, policy or notice for veterans, for instance, and you ask your colleague on your team who happens to be a veteran what they think of it, or even watch them use it, that doesn’t count. Your colleague probably owns a computer and probably has stable housing, for example, unlike Dominic who could count on neither. But more importantly, your colleague is by definition steeped in the language and norms of a bureaucracy; representative users are not. And in the case of the VA application that Dominic couldn’t use, VA colleagues also would not have encountered the “spikes and IEDs” that Dominic and pretty much every other veteran outside the walls of the VA did, because those colleagues’ computers were set up with the exact (and very rare) combination of Internet Explorer and Adobe Reader that would open the application. While it’s a good rule of thumb to have people on the inside actually use the outward-facing systems, this is not a substitute for the practice of actively finding and engaging with a properly developed sample of people who can tell you what you didn’t know you needed to know.

Go direct

One temptation in listening to the public is to rely on advocate groups as intermediaries. They can be enormously helpful. But this is also not a substitute for actively finding and engaging with a properly developed sample of people who can tell you what you actually need to know. There are some groups (the minority) who purport to represent populations that simply don’t do it very well; this is a philanthropy-driven ecosytem in which those with the most resources to engage with government are often those who’ve appealed most to the holders of charitable purse-strings (and yes, I’ve been one of those people, which is how I know!), not those who are most able to represent the population you’re trying to engage.

In the vast majority of cases, there is a critical role for these groups, but I’ve seen a very wide range of ability to accurately represent the needs of their users among non-profit groups, in part because there is rarely consensus among the population themselves, and in part because these issues are just complicated. One tactical example of this is advocates who pushed to include voter registration at the end of applications for SNAP. In theory, it makes perfect sense to increase the political power of low income people. In practice, it resulted in lots of people abandoning their online applications right at the end. The rules about who can vote are very different from the rules about who can get food stamps, and introducing a new set of eligibility requirements at the end of the process is confusing to many applicants. But it’s also scary for many: voter registration forms contain a lot of required language about how it’s a felony to vote if you’re not an American citizen; people with undocumented family members can see this as a huge risk. They just close the window. That’s people who not only didn’t register to vote, but now also didn’t get SNAP benefits.

An ACLU lawyer I met in Idaho coined a word that stuck with me: the advotocracy (though I’m not sure I’m spelling it right!) He worked on behalf of people with disabilities, and had come to see how the needs and desires of his clients often diverged from the goals of the organizations who were supposed to represent them (and yes, of course, he is one of those advocates!) He’d learned (partially through some very effective advocates, to keep this complicated) how many people with disabilities wanted more autonomy and freedom, even if it meant more risk in their lives. The government programs supporting them were so thoroughly designed to keep them safe that they often felt they weren’t able to fully live. He’d changed how he supported his clients, and saw some effective and aligned advocates around him, but also cautioned me to be wary of organizations that took a paternalistic approach to clients. To him, the advotocracy was a sort of rule by advocates that sometimes eclipsed the needs of the community to self-govern and determine their own fate. I’ve heard from administrators of a different state medicaid program for the disabled that the federal Department of Justice is suing them for not forcibly administering IQ tests in certain homes in order to ensure that every possible person with developmental delays is covered by the program. There are lots of people who don’t want that, they tell me, and I can imagine based on my experience in Idaho that that’s right. I’m not sure if this is a case of the Department of Justice listening to the wrong advocates – those pushing for full coverage in all programs at all costs – or not listening at all. But government’s relationship with advocates takes care and judgement.

The case of the Idaho lawyer illustrates one valuable role for advocates. The government program administrators changed their approach dramatically after an advocacy organization hosted an unusual day-long meeting. They recruited people with developmental delays and other disabilities and asked them to sit in a circle in the middle of the room. They invited administrators to stand in a circle around the clients. For several hours as the clients spoke about their lives, the government team were not allowed to talk. There were short breaks in which the administrators were allowed brief clarifying questions, but the vast majority of the time their only role was to listen. One client who’d been required to attend an adult education program explained that the program staff had been trying to teach him to tie his shoes for seventeen years. “I have velcro on my sneakers,” he pointed out. Another had been in an endless loop of being taught to balance a checkbook. “I haven’t balanced a checkbook in years,” an administrator observed, as he realized that the curriculum in these adult education programs was not only sorely out of date, but also far too rigid. It was fundamentally disrespectful of the autonomy and humanity of the people in the program. That same administrator told me that none of his colleagues left that room with dry eyes that day. They were profoundly moved by an in-depth, direct experience with people they thought they knew. Facilitating these direct government-to-public interactions is a great way that advocate groups can help with public participation and community engagement that provides fresh insights and leads to a focus on meaningful change.

If I’d asked them what they wanted, they would have said faster horses

If traditional public input solicits opinions, the question is what to do with those opinions, especially when they conflict. But even if they don’t, in a service design context, it’s not people’s opinions you’re looking for. “Did you like filling out this tax return? What do you think about the tax process?” The answers to questions like these do not really help you improve a service or make it easier to use. (I’m very skeptical of “satisfaction surveys” that a lot of programs use these days, in part because they don’t capture users who gave up half way through, and in part because they imply that a decent satisfaction rate means we can stop listening to users. There are often alternative metrics that show that significant improvement is yet to be made.) Alternately, watching someone try to file a tax return and noticing which questions are easy for them to answer and which are hard gives you useful insight into what to change, clarify, or even remove. This is observation of behavior, not solicitation of opinions.

This can apply to policy design as well as service design (and, as you may know, I believe these two processes should be far more integrated than they are today.) There’s an increasing body of evidence that giving people exactly what they ask for is often the wrong answer. Henry Ford is said to have quipped (though he probably didn’t): If I’d asked them what they wanted, they would have said faster horses. By giving people what they said they wanted he would have missed the chance to provide something that met people’s changing needs – for faster transportation in an increasingly urban and connected environment. In a policy setting, we see more and more often that taking advocates' demands literally can easily fall prey to the law of unintended consequences and fail to achieve the stated goals. The Americans with Disabilities Act, for example, doesn’t seem to have succeeded in protecting people with disabilities from employment discrimination, for instance2. Policies promoting pay transparency don’t seem to have resulted in better wages for workers.3 I share many examples of policies that result in perverse effects in Recoding America, generally because of a phenomenon I call “policy vomit,” in which the words of the policy are vomited, essentially undigested, into a service, without the benefit of thoughtful, user-centered design. Similarly, vomiting intentions directly into policy without the benefit of thoughtful, user-centered design can be equally unhelpful. Design is the expertise government should provide, not just deciding which of a wide variety of interest groups gets their way. Happily, when we thoughtfully design policies and services, we make more people happier in the long run, even if they’re skeptical at first because we’re not doing exactly what they asked for.

Let me provide an example in a government software context that I believe has resonance beyond software. Lainey Trahan of the Colorado Department of Public Health was working on replacing Colorado’s vital records registry. Users of this new system would need to be able to search for birth records. The program told her they needed 17 different views of that search, so essentially 17 different groups of permissions. Different departments -- human services, hospital registrars, birth registrars, field units, the state office, child welfare, etc -- all had different needs, and different roles within those departments also had different needs. The program had collected each of these as unique requirements, and Lainey’s job was to deliver on those requirements. She was told several times to just deliver the 17 views.

But Lainey had an instinct ask some questions. “Why does human services need to see the address but the field unit needs to not see the address? Would it be helpful for them to see the address? What do you guys do when you have duplicate entries? Wouldn’t it be helpful for the field units to be able to see that the address is different or the same so they could flag duplicates?” She asked the stakeholders a series of questions like that to get them to think differently about what they were asking for, and then made a big spreadsheet of all the fields they wanted the end user to see across all the views, and talked them through it. With a little negotiating, Lainey found she could accommodate all the needs of all the stakeholders with just four views.

What’s the difference between 17 views and four? Obviously, there’s a cost to the project for each additional view, both in money and time. And the bigger and more complex the software, the harder it is to debug, the harder to maintain, and the harder it is to use. The more different ways you have to do any given task, the more variation tends to crop up; one person does it this way, another does it another way, and ultimately the differences in those paths mean that down the road, different users make different requests for new features, and if no one is taking the time to understand what those users are really asking for, the way Lainey did, the software gets exponentially more complex. Had Lainey not made that seemingly small decision to push back on the requirement for 17 views, the project would have taken one more step towards the complex, clunky, hard to use software for which government is so famous. In the short term, each of the departments that had asked for their custom views might have been happy to have gotten what they wanted. In the long run, as the software’s performance degraded, no one would have been happy.

This practice goes beyond listening — it’s not just hearing complaints or desires and responding, but digging in, asking questions and clarifications that position you to go beyond response and into designing novel solutions. It risks confusion and disappointment — Wait, where are my faster horses? Where are my 17 views?— in the hopes of getting to something better. There are extreme and highly opinionated versions of this that inform a certain view of the job of governing, like former West Sacramento mayor Christopher Cabaldon’s perspective that it’s often a terrible idea to give people what they want. “If you were having a heart attack,” he once told me, “would the doctor ask you if you’d like to be cut open or shocked with electric paddles? No one wants those things, but the doctor’s job is to keep the person alive and as healthy as possible.” When a neighborhood is choked with cars and no one’s walking anywhere, he explained, and residents show up at the public meeting and tell you they want more parking, do you give them that? Or do you guide them towards a more walkable commercial area, which you know will lead to better foot traffic for your local businesses, lower congestion, healthier residents, better environmental effects, and higher property values? There’s certainly room for more “give people what they need, not what they want” in our governing, and Cabaldon was a very popular mayor despite his sharp rhetoric (he was unopposed in multiple elections), but this is not always either wise or practical. It’s certainly more warranted when the patient is having a heart attack, so to speak. There are certainly lots of areas where that metaphor is apt, especially in our efforts to combat climate change. We may not always be able to give people what they want in the short term. But it’s government’s job to keep the patient alive.

On surveys

We’ve mostly talked so far about open public input processes like notice and comment or public meetings. But one thing government relies very heavily on for input is surveys, which are often conducted with active outreach to a defined set of respondents. When I’ve talked about user research, many people think it’s surveys I mean. But as I recently explained to a friend, I spent ten years running Code for America, an organization known for its excellent user research capability, and I don’t recall a single time we ran a survey (I may be wrong!) We didn’t have anything against them, it’s just that our team didn’t see them as being particularly useful tools to provide the insight they needed for their work.

I have been heavily influenced by Erika Hall, the co-founder of Mule Design Studio and author of "Just Enough Research," who is known for her view that “surveys suck.” It’s not that they’re never useful, it’s that they are often misused and misunderstood. They're often seen both inside and outside government as a catch-all solution for gathering data, rather than one tool among many in the researcher's toolbox, and it’s quite hard to conduct them in such a way that will provide meaningful, accurate, and actionable insights. There’s the issue of asking questions people simply can’t accurately answer, like “Will you buy a product like this in the next 12 months?” That example comes from the world of market research, of course, but Erika points out that the answers to any question about a respondent’s future behavior should be considered very unreliable. Response bias is found in a wide variety of other circumstances too, and people very often misunderstand questions. The results of surveys are often used to support conclusions they don’t really support in any meaningful way. They are sometimes merely unhelpful, and sometimes lead decision-makers to dangerously unsound conclusions. This brings me back to the Michael Lewis quote we started with: “You never know what book you've written until people start to read it.” You never know what question you’ve written on a survey until people start to answer it and you have no idea what those answers mean.

One reason for this is that while surveys can sometimes help us answer the questions we know we need answers to, they don’t help us see the questions we don’t know to ask. They don’t help us learn what we don’t know we don’t know. My personal revelation on this topic came from the GetCalFresh team at Code for America observing SNAP clients applying for the program using the online application available at the time. There’s a question about household size, and a remarkable number of applicants stopped at that question. (That’s another thing you can observe without a survey too, by the way — mine the data for abandon rates at various pages or questions and ask why more people are leaving the application there than other points in the process.) But doing this observational, unstructured research, just following folks using the form, told the team that a very high percentage of people don’t know how to answer that question. They may have partial custody of their kids and don’t know if they count. They may live with their parents but take care of their own meals. They may not have stable housing, or they may live in more than one place, or have any number of life circumstances that complicate that answer. That insight led the team to rewrite and restructure that question significantly, and to test and iterate until they found a way of asking it that most people could answer. But think about the number of surveys that ask a question about household size without the nuances the GetCalFresh team ultimately built in. How would the surveyers know how to interpret that data if the options they provided assumed a life far more static and uncomplicated than the lives of their research subjects? Surveys are generally less useful than they are seen to be, but dramatically less so when used in the absence of complementary research methods to inform the survey design.

***

In wrapping this up, I want to reiterate the humility with which I offer these suggestions in the context of PPCE. If you’re responsible for service design (or whatever you call it in your context), I’m confident in recommending active recruitment of a diverse set of representative users, direct interaction with those users, digging in with further questions and observations to deepen understanding and resolve conflicts, observing over asking opinions, and the practices of design and product management to avoid policy vomit. But if you’re responsible for engaging a community in which a public works project needs to be built, and there’s understandable opposition, you have a very hard job. I’m offering lessons from a related domain that seem to have value based on my imperfect understanding of the problems. Experts who study novel forms of public engagement will better understand how to apply these principles. But this field is critically important given today’s challenges, and my hope is to spur healthy dialogue.

Comments are due today (Friday, May 17) but OMB says that to the extent practicable, they’ll take comments after the due date.

https://www.nber.org/programs-projects/projects-and-centers/retirement-and-disability-research-center/center-papers/drc-nb16-07

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/322836

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.38.1.153

I feel like an outsider coming from a software engineering background reading this. But I get a sinking feeling in my stomach. I feel bad that this level of explanation is needed. These projects just happen with no user research?

Do these projects have roles like “UI designer” and “product manager”? To me, this sort of research is just part of the PM/designer job. Are these projects operating with no designers, or no PMs, or are they hiring inexperienced designers and PMs?

If folks are interested, sharing the (hopefully more useful) non-Federal Register page (FR is wonky and sometimes clunky to use): https://www.performance.gov/participation/