There’s a lot to be said about the last week, and I’m still processing much of it. But there’s a mental image that keeps coming back to me, of a DOGE team member with his hands on a keyboard and eyes on Treasury’s federal payment system.1 (To be clear, I’m merely conjuring this image from very vague reporting. I have no first hand DOGE contact.) This image has correctly raised alarms, for the reasons others have covered.

Under different circumstances, and with different people, I’ve seen these moments before.2 I wrote about one of them almost ten years ago, and I want to share it here, not because the story will necessarily turn out this way this time — the people involved may have very different motivations — but because I want a reminder that empathy and respect have a way of showing up in the crazy world of government, where things are not as simple as they seem.

Remember, I wrote this in 2016:

I had a small role in recruiting this man. He’d spent the last ten years leading engineering teams on a consumer product you’ve probably used, and he’s just arrived in DC to work with the federal government. He started on Monday, and it’s now Thursday night. I run into him at an event. He arrives late, and looks shellshocked.

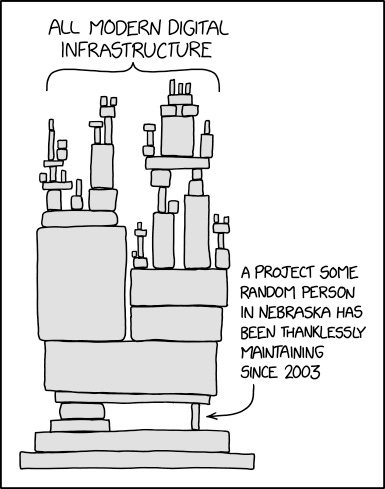

How’s it going? He’s struggling to put words together. I’m worried. “I just left the office. I think everything’s going to be okay.” What is he talking about? “For the first day and a half, nothing. Then it was ‘go to this agency and help them with this thing. It needs to go live on Thursday and there’s a problem.’ Yes, there was a problem. The data the service relied on….I’ve never seen a database like that. Ever.” What do you mean? “1993. The guy couldn’t find any other way to make it work. The vendors would have taken too long even if someone could justify the budget. So he just hacked it at nights and over weekends. Used whatever he could find and taught himself how to use it. The machine is ancient. The software has just been running since then. I’m amazed he managed to keep it running this long. It’s a miracle. Either no one knew, or no one cared — my guess is that they were just happy to have something that worked at all. The guy’s been keeping this going like this…I mean…I had no idea…I’ve never seen….” He’s shaking his head and looking past me.

What happened? “First we just had to make sure we could get the data out somehow, make sure we had a copy. I mean, these records…they’re the only copy. The whole system relies on this. People rely on this. To help real people. People who need help. If it had failed…” He really is in shock.

“I’d just never seen anything like this. I was afraid if I even touched it, it would all go poof. We got it out. It’s okay…. It’s okay now…But this guy…He’s been keeping this together for 23 years…”

For a minute, I worry that he’s angry. And that he might be angry at me for encouraging him to take this job. But I look in his eyes and it’s not anger, it’s awe. Respect. Admiration and gratitude for a public servant who has achieved the impossible. Made things work in spite of the rules, not because of them. “He made it work. He’s the only guy who can run it. He knows it wouldn’t work without him so he’s deferred his retirement. I mean…he’s extraordinary.”

Extraordinary. A Silicon Valley technologist, the kind of person we champion as a savior of government, thinks that a career civil servant beyond retirement age with sorely outdated technical skills is extraordinary.

That career civil servant’s name is Jed. The system he started building in the 1980s and maintained for decades before my friend came along was called VACOLS, the Veterans Appeals Control and Locator System. It started out serving just 400 users, and expanded to 17,000 across multiple parts of the VA system. Logic Magazine later interviewed him, and the backstory is well worth a read.

Originally, the system’s primary job was to know the locations of the physical files of the 30,000 or so veterans who appealed their benefits decisions. Over time, VACOLS grew and became more complex as [Jed] iterated and added modules like courtroom scheduling and video hearings. He would gather requirements directly from judicial review officers, judges, and administrators, deploy a prototype, get feedback, and deploy again ... .Now, it’s keeping track of virtually who has the claim and what the status is and what part of the process it’s in.

I don’t want to romanticize Jed or VACOLS. Appeals under this system took three to seven years, in part because of the rules that allowed for an open-ended process that could essentially restart at any time, which have since changed. That’s too long. But listening to Jed, you understand how it got that way. And it wasn’t because Jed was incompetent. He was highly competent for the work he was charged with.

There’s no need to imagine how Jed would have reacted to the “fork in the road” email. He’d been eligible for retirement for some time when my friend encountered him. He’d stayed because if he left, the appeals process for veterans benefits would have fallen apart. It took a while not just to migrate VACOLS, but to work through the legacy appeals. It sunsetted only recently. Jed is finally retired.

Treasury's federal payment system can’t be as fragile, bespoke, or dependent on one person as VACOLS was (I have no knowledge of it), but I imagine this DOGE employee in partial shock from the complexity of it. And I imagine DOGE teams had their hands on other such systems this week, ones that bore the hallmarks of decades of both care by dedicated public servants and neglect by a system ill-suited to the task of operating in the modern era.

What I want to imagine next is this person, new to government, meeting Treasury’s equivalent of Jed, and sitting down with him for the rest of the day. If he would just listen, I can’t imagine he wouldn’t find Jed extraordinary.

The payment system actually sits at the Bureau of Fiscal Services, a component of Treasury, if I understand correctly.

I am not trying to draw an equivalence between what my friend did to help VACOLS and what is happening at Treasury and elsewhere now. But there is a path the new additions to government could choose to take.

The problem with this framing is that Jed is only valuable because the system is valuable. Our current overlords want to burn everything down.

If you want to burn a building down, you don’t need to stop and appreciate the architects.

Excellent framing and I hope more members of the public come to learn of and admire the commitment of the many Jed’s in govtech. That said, for any of the new special gov employees to learn from Jed, they’d need to WANT to learn from him. In other words, they’d need to share his goal of more effective government and…I seriously doubt they do. Their actions, the nature of their shock and awe engagement with the current staff, and the reports of who they seem to have been in private life all suggest that they are simply don’t care if they break things OR perhaps are there explicitly to break things. Dan Hon had an great thread on BlueSky that maintained it is actually the motivations of decision makers that determine the outcomes of such efforts - is there ANY indication that the folks currently involved have a goal of improving gov outcomes?